The Backdoor you're comfortable with

Data flows are power flows, and jurisdictions are never neutral. Europe's dependency on US tech infrastructure creates the same structural risk it criticises in others

Over the past week, two pieces of content have been shaping the mental context for this article: Keith Rabois’ viral post on Airwallex, and Micode’s latest documentary on CIA interference in French tech. One comes from the heart of Silicon Valley (Miami?), the other from a leading French YouTuber doing investigative work.

Together they sketch the same uncomfortable picture: data flows are power flows, and jurisdictions are never neutral. This pushed me to revisit a question that Europeans often avoid because the answer is geopolitically inconvenient.

Two things can be true at once:

- the US remains the centre of gravity for global tech

- Europe should be asking itself the same hard questions Keith Rabois is raising about China, just applied to our own dependence on the US.

We talk about digital sovereignty, publish strategy documents with more acronyms than verbs, and then… grow our AWS spend and move more workloads to US infra.

Keith’s recent thread on Airwallex stressed this, but on the Chinese side.

1/

— Keith Rabois (@rabois) December 1, 2025

Cool growth chart. Have you disclosed to US customers like @Rippling, @Billcom, @TheZipHyouQ, @brexHQ, and @Navan that you’re quietly sending their customers’ data to China?

Airwallex has become a Chinese backdoor into sensitive American data like from AI labs and defense… https://t.co/03xJRQDlXF

In his words, Airwallex, a global payments and financial technology company, is "a Chinese backdoor into sensitive American data," alleging that US companies have not been told that their financial operations, payroll flows, and vendor payments are being processed by a company whose staff, infra, and shareholders fall under Chinese National Intelligence Law.

His core argument is simple: if data passes through a jurisdiction whose laws allow secret state access, that government effectively has a backdoor, regardless of the company’s intentions.

Replace "China" with "the US" and Europeans suddenly find themselves staring at a very familiar problem. We pretend not to see it because the cognitive dissonance would make half our economy implode.

Is the US doing to Europe what China is doing to the US?

When Europeans hear "China has a backdoor into US tech flows," they don’t just nod along, there’s this eerie sense of familiarity, a quiet recognition that the logic feels a little too close to home. The structural mechanism is almost identical though and here are 3 pieces of legislation to prove it:

- The US has FISA 702: This allows US intelligence agencies to demand data from major cloud providers, email platforms, and large SaaS companies, even when the target is a non-US person abroad. These orders are secret, and the individuals affected never find out.

- The US has the CLOUD Act: This legislation requires US companies to hand over data they "control," even if that data is physically stored in Europe or elsewhere. In practice, it means jurisdiction follows the company, not the server location.

- The US has Executive Order 12333: This governs intelligence collection conducted outside US soil and does not rely on warrants or court oversight. It allows broad interception of data moving through international networks. In other words, some European data never needs to touch a US server or US company to be intercepted.

This isn’t a new debate. Two agreements that allowed European companies to send personal data to the US (Safe Harbor and Privacy Shield) were struck down 5/10 years ago because the EU’s top court ruled that once European data enters the US, it can be accessed under American surveillance laws in ways Europeans can’t contest or even see.

It’s the same underlying logic as Keith’s argument about Airwallex: once your data enters a jurisdiction where intelligence agencies can secretly compel access, you’re no longer dealing with "just another vendor", you’re dealing with that state’s interests and that’s exactly why I feel that eerie sense of familiarity when hearing his critique.

A 1-to-1 comparison?

If you read Keith’s critique of Airwallex as a highlight of data and jurisdictional dependency, it's a very lucid observation. Let's have a look at how this observation maps to the EU specifically.

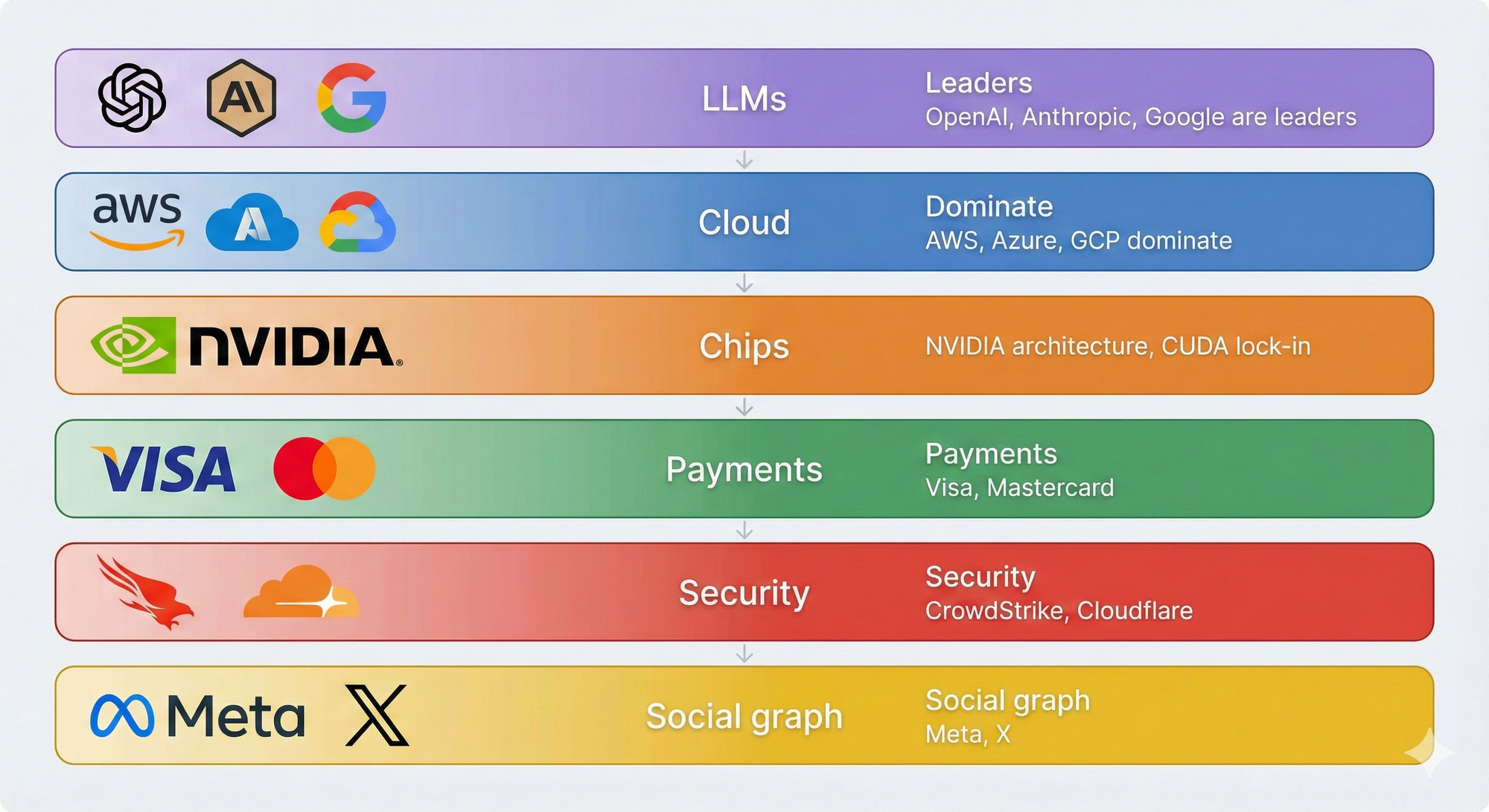

| Concern Keith raises about China | European concerns about the US |

|---|---|

| Engineers in China can be compelled to cooperate | US cloud engineers can be compelled under FISA |

| CCP obligations can compel Chinese entities and citizens to cooperate, even abroad | US law applies extraterritorially through the CLOUD Act and EO 12333 |

| Critical US data flows through Chinese infra | A huge share of EU data flows through US infra/apps |

| Customers unaware of risk exposure | I would assume the same in the EU if you survey customers |