Tax the past, fund the future

Zucman's tax on unrealized gains risks penalizing entrepreneurs, forcing asset sales and driving startups abroad. France should adopt nuanced tax policies supporting innovation, not stifling it

France has its own 'Zuc'. Not the one who's building superintelligence and flooding your parents' feed with AI, the other one; economist Gabriel Zucman, who wants to connect your unrealised investment gains to the tax office.

His proposal for a 2% annual tax above €100 million has a clear goal: addressing the regressive tax system where billionaires often pay proportionally less than ordinary citizens. However, if we do not separate rentiers* from entrepreneurs in this discussion, we'll end up taxing paper wealth and sending the wrong signal to founders.

*A note for non-French readers: a “rentier” is someone who lives off income from investments or property, essentially income without working. English does not really have an equivalent, which is telling.

The discourse recently crossed over into my startup/tech world so here are some thoughts: Not all fortunes are created equal. A startup founder’s paper gains and a heir’s passive income might look similar on a spreadsheet, but treating them the same way risks crushing the very ecosystem France has successfully built up over the past years.

1) The French hook

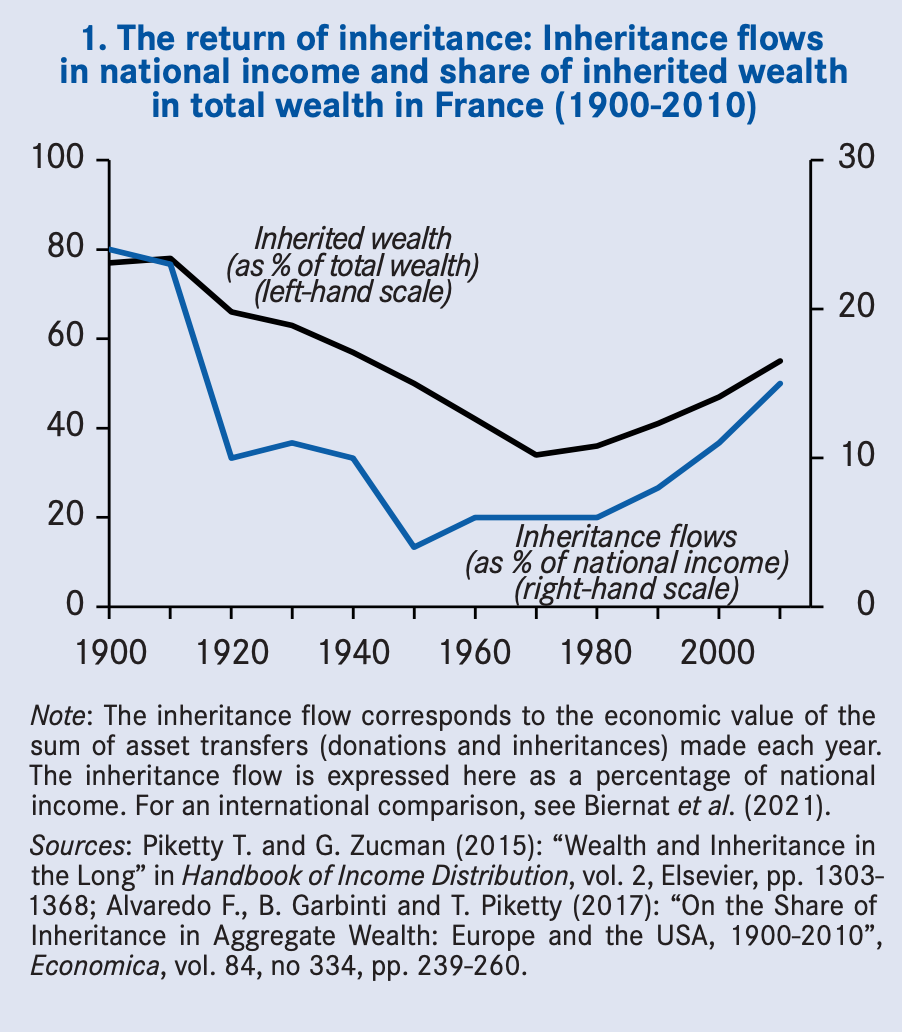

In France, wealth at the top is mainly dynastic, not entrepreneurial. In the early 1970s, inherited wealth was about 35% of France’s total private wealth; today, estimates put it near 60%.

In France, the upper echelons remain dominated by heirs of industrial and luxury empires (think Hermès, Chanel, L’Oréal). Data from the national statistics bureau (INSEE) reinforces this trend and the growing weight of inheritance in today’s wealth distribution. Europe’s long established dynasties help explain this persistence: a study (Barone & Mocetti) on Florence found that the city’s richest families today are largely the same bloodlines that dominated 600 years ago. In short, old wealth in Europe, and especially in France, sticks around. The self-made billionaire examples in France are far and few: Xavier Niel, Patrick Drahi, and Mohed Altrad are names that come to mind.

By contrast, the United States has taken the opposite route. As shared last week in the Forbes 400 ranking, US billionaire ranks are mainly self made: about 71% of the 2025 list (up from ~40% in 1982), with especially large numbers coming from technology and finance. This year, there were 14 new entrants into the ranking, all self-made, 10/14 from tech. As a point of comparison, the US has about 3x more billionaires per capita than France. (FR 60/68m, US 900/334m), 9 out of 10 of the wealthiest billionaires have built their wealth in tech.

Meanwhile, when you look at tech and startups, France has produced plenty of entrepreneurs, but these biggest successes have happened elsewhere. Consider Datadog (founded by French entrepreneurs, built in New York and now on the NASDAQ) or Snowflake (co-founded by two French engineers, built in the Silicon Valley and listed on the NYSE). The current market cap of Datadog is about $47 billion and Snowflake is about $74 billion. The French tech unicorns are collectively paper-valued at around $80bn...

I'd like to make sure that the next Datadog or Snowflake doesn't have an extra reason to leave France and the reality is that those next founders will make up their minds long before ever reaching that level of wealth.

The signal matters and policy should reflect this. If France is looking to tax its elites for a lack of better options, France should focus on dynastic, cash-yielding wealth, not self-made founders. Figuratively, builders are already taxed when their buildings are paid off, they shouldn't be paying for the future build with the bricks they are laying.

2) Entrepreneur vs rentier

Not all wealth behaves the same.

- Entrepreneurs accumulate capital actively: they take risks, invest countless hours, build companies, reinvest earnings, and usually hold illiquid equity until a rare liquidity event such as a sale or IPO.

- Rentiers accumulate capital passively: they inherit wealth or park money in diversified, income yielding assets such as dividend stocks or real estate, often enjoying regular cash flows without much active involvement.

Taxing both types of wealth as if they were identical shows a total misunderstanding of how this value is created. This distinction matters for fairness, upward-mobility and growth. It matters even more in a globalized world, where individuals have optionality...

- Heirs and owners of land are less likely to move away as much of their wealth/real estate is tied to France.

- Entrepreneurs and high growth businesses can relocate if the grass is greener elsewhere. For France, that means we need to be careful not to push builders out with unfriendly (euphemism) tax policy.

The policy priority should be clear: keep our entrepreneurial talent at home.

3) Zucman’s wealth tax: the design flaw

The goal of the 2% tax is to stop the buy-borrow-die strategy, where the rich live off loans against their wealth and avoid income tax leading to lower effective tax rates.

The idea sounds straightforward, but here is the miss: the plan assumes liquidity that many of our most successful entrepreneurs don't have. At a €100 million threshold, the tax as designed does not distinguish between an inherited real estate empire and a founder’s stake in a pre-IPO startup. A 2% annual tax on a liquid €100 million portfolio might be paid out of dividends or by selling a small portion of assets (which I think I'm still against?) while the latter might be a 20% stake in a company that is still burning money.

To put this asymmetry in perspective, consider a 10 year scenario for two archetypes:

- Rentier, heir to a large quoted company. Suppose they oversee €100–150 billion in various assets, like large stakes in Chanel or L’Oréal. Such a portfolio might yield roughly €1–3 billion in dividends each year. A 2% wealth tax on, say, €125 billion would be about €2.5 billion a year, which is on par with the annual cash income. Over a decade, they would pay on the order of €25 billion in tax but also receive perhaps €20–30 billion in dividends cumulatively. They are paying a lot, but their wealth itself could theoretically offset this amount?

Now an open question to the economists: With the 100m net worth example, a 2% tax would require to free up 2m/year, if the assets don't produce such a yield, is the state ready to send the terrible signal of forcing people to sell assets to fund the tax? Is this something desirable? Why would these wealthy individuals keep the stocks in the first place if the full value creation is captured by the state?

- Founder, pre IPO stake. Now take an entrepreneur who owns 20% of a high growth startup valued at €1 billion, so €200 million on paper for them. The company is reinvesting everything and is not profitable, so the founder’s annual cashflow from it is zero. A 2% tax on €200 million means a €4 million bill each year. Over 10 years, that is €40 million in taxes, but €0 in cash generated by the asset to pay it.

In recent SaaS IPO cohorts, the median founder CEO stake at IPO was only about 10.6%. At that ownership level, a unicorn founder is instantly liable to pay this tax, even before they have gained liquidity.

In the end, you have not achieved justice, you have penalized those who are innovating, reinvesting and creating new value, while those who are passively surfing on old fortunes find workarounds.

FYI: 0.07% of venture-backed software startups founded in the 2000s reached the $1 billion threshold, meaning roughly 1 in every 1,538 startups achieved unicorn status. Leave the few entrepreneurs who actually reach this step alone, you're picking the wrong fight - let a man dream!

4) What could we do

- Exempt founder equity until liquidity

Don't tax unrealized gains from active business ownership until there is a liquidity event such as a sale or IPO. At that point, tax the gains or with a slight deferral, as we currently do. To encourage the capital and talent of successful ventures to stay in the ecosystem, pair this with incentives for founders to reinvest in French startups. Oh wait, we're already doing this: the 150-0 B ter/apport cession mechanism already allows this. - Refocus on inheritance and holding structures

If France wants to curb the rise of inherited wealth and preserve a credible meritocratic story, it should:- Celebrate self-made entrepreneurs, instead of calling them parasites, as the European LFI député Anthony Smith just did over the weekend.

- Tighten the screws on dynastic wealth mechanics so that the top does not enjoy significantly lower effective tax rates than those who work for a salary.

- Stop viewing financial success as something to be frowned upon. As Coluche, a famous French comedian said: "If we listened to what is being said, the rich would be the bad guys, the poor the good guys. So why does everyone want to be bad guys?".

- Enforce a minimum effective tax on rentier income.

To my knowledge, there is no rule guaranteeing a minimum effective rate on these rentier cashflows each year. A sensible reform would be a minimum tax rate on large passive income streams, not the entirety of the net worth as suggested by Zucman. For example, ensure that once an individual’s dividend, interest, and rental income exceeds a high threshold, the average effective rate paid is the top bracket + x%. This way, high net worths contribute every year from liquid income without forcing sales of assets in a higher proportion than they currently do. - Give everyone a stake, not just a safety net

Tax policy is France focuses too much on the Bernard Arnaults of the world and should focus more on how to lift up those at the bottom. Giving every child a small capital amount to start life (like the recent Trump accounts), is a great idea. Each child gets $1,000 in a government seeded investment account. Families can add to it, and it is invested in index funds to grow until the child reaches adulthood. France could implement a similar program, let it grow untouched except perhaps for education or starting a business, until the person retires or hits a milestone. This policy would democratize access to the kind of compounding that the rich benefit from, and it would familiarize ordinary citizens (and the left?) with equity ownership. Fund this by channeling some revenue from the inheritance and rentier taxes above. If inequality is a gap in assets, not just income, then we should give those with zero assets something to start with. - Financially incentivise entrepreneurship

To truly signal that we value innovation, France could establish a US-style QSBS policy, by offering tax exclusions on gains if the stock is held for a number of years (not deferral, exclusion!). It tells entrepreneurs and venture investors that we want you here, and we will reward you for betting on our economy.

5) Why are we having this discussion in the first place?

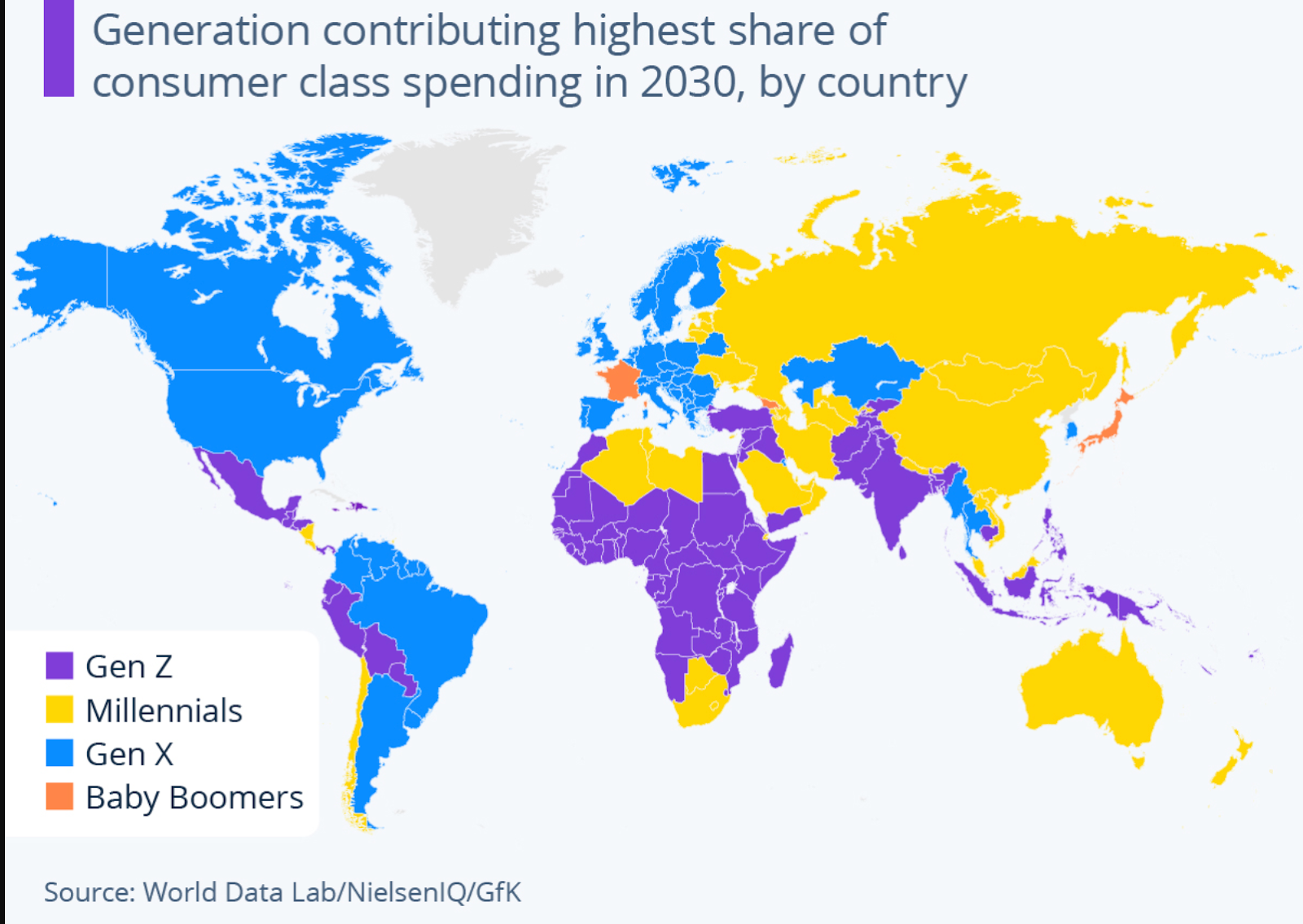

If we’d done grown-up pension reform, I wouldn’t be writing this. We're looking for money on the sidelines instead of addressing the elephant in the room. The existing system is just a ponzi that people refuse to call out as such, the bottom of the distribution (the new generations) is squeezed, and the state is hunting for cash to fund itself beyond pensions.

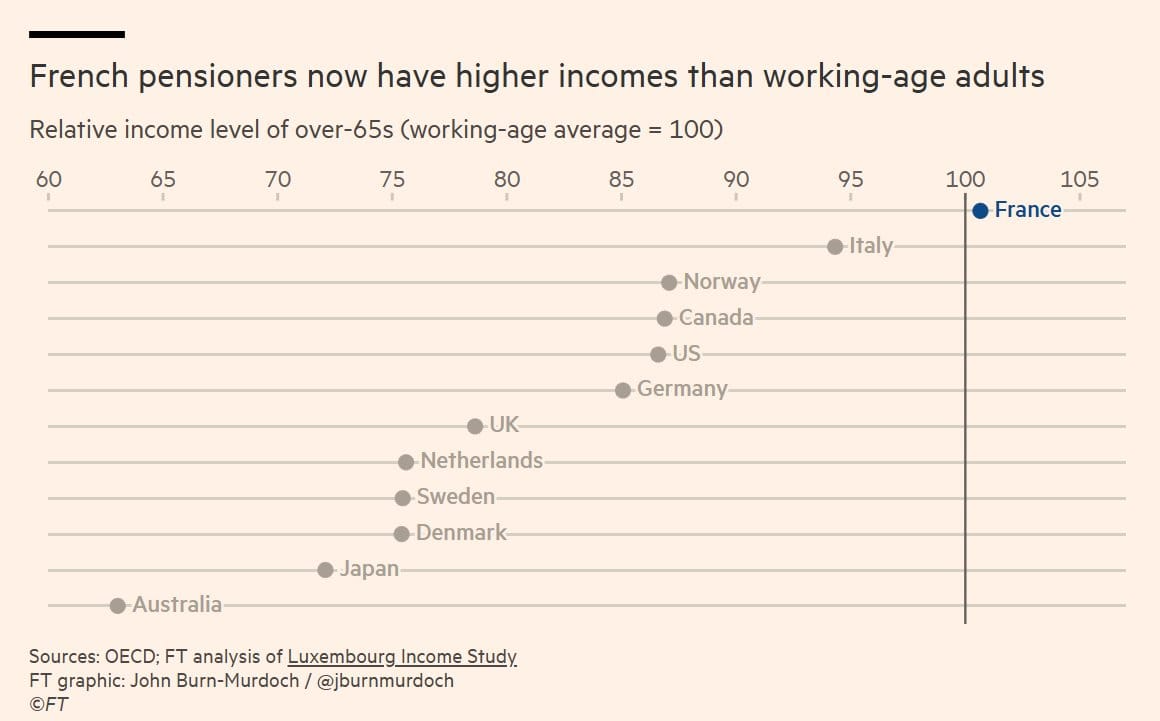

Over the weekend, the Financial Times shared yet another damning visual showing how French pensioners are more wealthy and consume more than the working class. How can you in your right mind defend retirement at 62 (even 60 - caugh caugh Manuel Bompard) when seeing this? The framing is off.

Fix the right things first and then we can also focus on hitting rentier cash flows and intergenerational transfers for more social justice if need be. The left in France should also embrace the idea of wider capital ownership as part of the equality agenda. You cannot criticise that the rich get richer from stocks and then deny those same stock market gains to everyone else. If we truly care about equality of opportunity, we should help everyone, not just the rich, benefit from capitalism’s wealth generating tools. One word: pensions should shift to capitalization and we should index pensions not on inflation but wage growth - this would be true social and generational justice. While Zucman aims to gain 15bn with his tax, the re-evaluation of the pensions in 2024 cost 20bn alone...

8) 'Yes, but' counterarguments

- "The optics, it's a question of social fairness"In aggregate, only a modest number of French taxpayers relocate for tax reasons each year. The next Datadog or Mistral could choose San Francisco over Paris if they feel a wealth tax targets them unfairly. Yes, France can build a US-like exit tax but, in my opinion, the best policy is to avoid creating the incentive to leave in the first place.

- "Unrealized gains are the only way to reach their wealth"Yes it's true, many billionaires optimise “income” on paper but there are other ways to ensure the wealthy pay tax regularly. One is taxing the cashflows they do receive, for instance dividends from their corporations or rents from their properties, with a minimum effective tax on those flows as suggested higher up. Another is taxing wealth transfers aggressively when wealth changes hands or generations. If we must address buy> borrow>die, we can look at taxing large increases at death or limiting how much someone can borrow against assets without tax. It feels we have options that target rentiers far more precisely than a blanket unrealized gains tax.

- "This hits almost nobody, why worry"Yes it's true, the tax would only hit a tiny number of people in France but policymaking is about principle and precedent as much as immediate scope. The concern isn't that France cannot collect from a couple billionaires. If you're a founder dreaming of building a €10 billion company, such a policy sends a message to every aspiring entrepreneur that if you succeed spectacularly, you will be singled out. Ambitious people are forward looking, we want their dreams to play out on French soil.

Tax the right wealth, the right way

A fair tax system recognizes how wealth is earned and how it behaves. We should tax rentiers, owners of passive, inherited wealth on the steady income and advantages their assets yield. We should tax entrepreneurs too, but at the point of liquidity, when their success becomes tangible and liquid, and in a way that incentivises them to reinvest in the next generation of ventures.

In short: You don't confuse rentiers with entrepreneurs. Our tax code shouldn't either.

Becoming a billionaire founder is not a moral problem in my view but converting that into multi-generation untaxed optimisation is (Florence anecdote style). The next generations should always compete more on talent than on last name, if Bourdieu's "capital social" is anything to go by, that should already be a strong headstart!